There are very many species here in Australia that could terrorise you. Sharks, jellyfish, and a myriad of sea creatures in the ocean. Crocodiles in both salty and fresh water. A rainbow variety of snakes across the sand and land. Spiders that lurk in places where you are most vulnerable. Cassowaries will headbutt you if given the chance, kangaroos will kick you, and I’m even positive there is an animal that knows karate. Echidnas will prick you, a platypus will poison you, and dingos will take your babies, showing even the cuter animals like to dance with danger. Though the kookaburra may not have the aforementioned attributes of being venomous, stealth, or having the knowledge of karate, our family recently discovered the kookaburra’s greatest strength – psychological warfare.

Part I: George’s Arrival

Usually, the worst thing about springtime at our family home is the threat of severe allergies from the camphor laurels and native trees that thickly surround half of the property. It is without a doubt that if my brother makes the pilgrimage home in the second half of the year he will surely leave with a runny nose and red, itchy eyes. But in the Spring of 2020, a new threat found its way into our lives.

It all began with what I’m sure developers could assume was a bit of “tree trimming” but was in fact more of a Ferngully-style deforestation. The land behind the gully that ran along our house was purchased by a developer who, to clear more land for housing, knocked down so many trees that we could now see light through what used to be a very dense bit of bush. It was just after that, the kookaburra arrived.

Alongside turkeys, wallabies, the occasional fox, and many native birds, the family home had always been frequented by kookaburras. But that spring one kookaburra became a regular, so regular that my father named him, George. Had we known what he was capable of, we would’ve given him a much more villainous name. The name George isn’t associated with tyranny and leans towards more wholesome vibes – George Jetson, Georgie Porgy, George Forman, George of the Jungle, George Clooney, even Curious George. At first, he was a novelty; “oh look at the kookaburra he’s all fluffed up”, mum would say. But she later changed her tone – he was playing the long game. My brother stated upon reflection of George’s arrival –

“I remember coming home and meeting him (George) for the first time… It had been a lonely long year and I ventured home feeling far away from my friends, and then he came to my window. I thought could this be a friend from afar? We spent a great time together, but then he betrayed me, became obsessed, vicious, and controlling. I couldn’t sleep, (I) couldn’t breathe by myself.”

A quick fun fact about kookaburras before we continue, their mating season is from September to January. Though this information isn’t particularly draw-dropping, it did coincide with the previously mentioned “tree trimming”. This is an event I believe we will continue to look back on and ask ourselves, “what if?”, similar to how I believe those professors who rejected a young Adolf Hitler from art school must have felt.

Put yourself in George’s shoes: it’s peak breeding season, his family have recently lost their home, and he’s looking for someone to blame. Someone to pay. And so it began…

Now if you’ve lived in a house with windows, which I’m sure is most anyone who isn’t a burrowing mole, you’d know that all too familiar sound of birds hitting glass. Sometimes it just wouldn’t register and they’d fly into it, giving themselves a pretty bad concussion. Other times birds would take their reflection as a threat and attack the window. This was our initial introduction to George, but he wasn’t like those other birds. George was a cunning kookaburra. He didn’t accidentally misconstrue his reflection for another bird, he saw beyond the glass, into our home.

At first, he would attack the living room window. A classic window. It was large and really only had a white wall behind it and minimal movement. This is the window an amateur would fly into a few times before realising it was a dead end. But George worked on it. Knocking, and knocking, and knocking. His persistence of course raised alarms at first, “what if he hurts himself? Is he okay?”, but these quickly grew into further concerns of, “how long can he keep this up?” and “by God, he’s ripped the screens, will he break the glass?”. Or can he break the glass? And if he can, what will he do to us once he’s in.

After visiting the living room window once a day for a few weeks, George moved onto bigger and better things. He started on the living room door. Rap, rap, rapping at the door, quoth the kookaburra, a little more. It was at this point mum felt it was time to reason with him, and when he came around, she would head outside to convince him to leave with a polite shoo-shoo. A bad move.

George made himself scarce for a few days. It gave us hope that he was, as suspected, just a dumb bird after all. But as Christmas drew nearer, so did George’s wrath.

Part II: When George Attacks

I am unsure whether Stephen King, the Grinch, and George were in on some conniving plot to ruin Christmas, but it sure seemed like that.

As George returned to frequenting our windows, it became more and more evident he was intent on destruction. He started with the screens in the lounge and living areas, moved onto the kitchen ensuring he meticulously drilled holes into them as well, and swiftly made his way around the house to the bedrooms. After destroying several full-length screens, we tried to defend ourselves with brooms and the occasionally thrown thong, but George showed no fear. You could approach him, and he wouldn’t flinch. Tell him to leave and he would laugh in your face. Threaten him with an inanimate object, and he would remember you forever.

My parents thought if they removed the screens, it would be enough to end his reign. It was not. Even upon their removal he’d return and squat along the windowsill banging and banging. George’s knocking had gone from frequent to excessive. He expanded his reach, and extended his hours, like anyone excelling in their chosen field of business would. From the early hours of the morning, George would locate the window of any occupied bedroom in the house and engage in an uncalled wake-up notice. Everyday. Again, and again. I know anyone who has experienced extreme sleep deprivation would know the toll it can take on you mentally and emotionally, and it appeared George knew this too. Every morning, without exception, George would be there from 3am to 4am. He would screech and bang until he woke us, and then upon realising the household was up and working, he would perch himself up in the Poinciana, on a branch, where he could fully view the comings and goings of our home… and wait.

Desperate for an answer, my parents researched kookaburra facts, deterrents, bird catchers, and wildlife experts. Though due to the festive season, the phone lines of those who could help us were dead. So, we bunkered down.

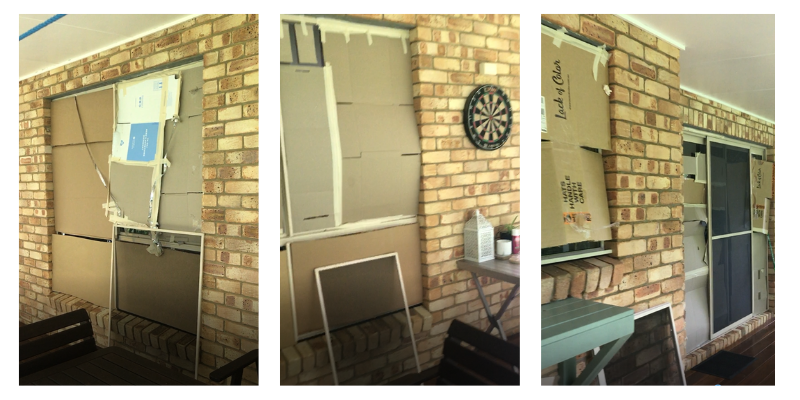

My father cut up spare boxes and bordered up the windows in our house that George would attack. But George would find any gaps and still attack the glass at all hours of the day. Eventually we were completely bordered in. My mother hung up reflective owls with large yellow eyes and sparkly strips along the veranda, but he would attack them piercing holes in their centres, slobbering along the sides, and disfiguring the eyes of the owls. My brother even sprayed bird repellent on George’s favourite spots in the tree and around our house. But George would return to each of these places after a day or two, with the rainy season making it difficult to spray deterrent effectively.

We spent our Christmas locked down. Surrounded by cardboard boxes like we were hiding some illicit indoor activity. In the dark. As we opened Christmas presents and popped Christmas crackers, we knew there would be no afternoon drinks on the balcony or wide-open windows of fresh air this season. ‘Twas the season to be wary.

Image 1: note the slobber from George dripping off the reflective owl.

Image 2: The reflective owl when it was first placed on the veranda.

Image 3: The reflective owl in Image 2 after George had attacked it and disfigured it.

Part III: George’s Revenge

We knew George was aggressive, but we didn’t know he would be vindictive. His psychological warfare wasn’t restricted to sleep deprivation alone. He began gaslighting the family, specifically targeting those who had thrown thongs to scare him off when he initially arrived.

Items on our balcony started disappearing. Often shoes would be removed and thrown all over the backyard. Sometimes they wouldn’t appear until several days later, allowing us to think we’d misplaced them just long enough to send us into a frenzied spiral of doubt. We’d find these items discarded in far off corners of the backyard that were barely touched, only out of luck or because my dad was hoping there would be some passionfruit for pavlovas amongst the weeds on the back fence.

Then one morning, it was quiet.

It was quiet, and the family celebrated.

Mum was cautious but optimistic. Dad was ready to finally pull down the cardboard and let light into our house again. My brother, who was clearly suffering from Stockholm Syndrome, even began to miss George. And as we slowly began to rebuild our lives in what we thought was a George-free world, he returned with a vengeance. He would peck, bang, and screech, slobbering over the windows and veranda in his hysteria. So even when we were away, we knew he had been. Living in fear of another early wake-up, another attack from George, another psychological tactic.

The new year came and went. George came and went. Around June of 2021, we thought he had grown weary of tormenting us. We thought he had returned to his family whom he was protecting. We thought he would leave us alone. But as the kookaburra mating season returned, so did George’s wrath.

Spring sprung along with mum’s new orchid. Since sightings of George had been few and far between, our guards were down, and our plants were out living freely on the veranda; a part of our house that had been emptied as a tactical defence move only a year prior. Then one afternoon, as mum was busy preparing for another wonderful Christmas, she came home to find a decapitated orchid, surrounded by bird slobber.

Out of fear for our Christmas, for our sanity, we had to act. Boarding up our house and screaming for George to leave was no longer an option; after the discovery of our neighbour’s toddler son being called ‘George,’ we were actively trying to reduce how often we threatened and cursed his name. Desperate, my mum reached out to any and all wildlife experts. Lucky for us, Tom responded. Tom made it known he was a busy man, knowledgeable about wildlife but hardly affordable. He reiterated that his business was costly, he was costly, but when adding up the cost of replacing screens and our sleep cycles or removing the assailant, the math pointed to Tom.

Luckily Tom could slot us into his clearly hectic pre-Christmas bird removal schedule. He came out and surveyed the area. Despite having visited and knocked every morning for several weeks, George was nowhere to be seen. George hadn’t come this far terrorizing our family to be grappled by some khaki-laden bird watcher, no sir. It felt like Tom was in on George’s conspiracy and noted that his services may not be appropriate for our property. But we persisted. After begging him for any tips on how we could save Christmas from another dark and dingy bunk-in, Tom assembled a barrier around our house. It was the flimsiest and saddest excuse for a defensive strategy. We believed there may have been a mutual assumption of craziness, with Tom thinking our kookaburra terrors had been grossly exaggerated and us supposing that a bunch of sad, saggy streamers that crisscrossed their way around the house could deter such a vengeful and devious beast. Tom assured us they would work, and if they didn’t, he said he would return with a humane capture plan, of course at a price. And then we waited.

We waited with bated breath, knowing nothing had stopped George in the past. Knowing he had the tactical know-how to avoid any attacks thrown his way. Knowing this could be another one of his games. And as we sat and enjoyed our Christmas Day prawns and presents, we watched as George circled the house between shining disco-tech dancing streamers that intermittently blinded us, but he never came any closer.

The sad streamers remained, and so did George, but he didn’t approach. He continues to do fly-bys, checking in regularly. But whether those streamers will keep him away indefinitely, we are yet to know.

Epilogue

After over 30 years of serenity, it’s hard to believe that a kookaburra has haunted our family home for almost 18 months. We have endured the extremities of what our nation’s famous cackling kookaburra can do, despite their seemingly jovial character. And we know we aren’t the only ones being harassed by these locals. During our in-depth research, we found numerous accounts of other Aussies who have endured the same psychological warfare from kookaburras as we have from George. Despite all the kookaburra terrorism that seems to be plaguing our nation, there are no answers to eliminating the issue. My mother still quietly wishes that each bird-like roadkill victim she drives past is George. My father still plots various ways he could ‘remove’ the bird-terrorist from his property without being blacklisted by the RSPCA.

But why did George choose us? We weren’t the ones who knocked down the bush, we were the ones fighting to protect it. Why didn’t he attack the neighbours and the other close-by buildings? We were the only ones afflicted by George’s madness.

I often ponder whether it was revenge for some offensive comment about kookaburras we made a few years ago, or because we had cursed him in a past life. If only we knew why George chose us, so we could right the wrongs and we could all live together peacefully.

One of the most Googled questions in our household over the past year and half is ‘how long do kookaburras live?’ the answer: too long. Twenty years. And of those twenty years, they mate for life, from around the age of three. So though George has been quiet, we know there is a chance, a high chance, our home may be troubled with his aggression for many, many, Christmas’ to come.

– Courtie